Inside Africa: Rwanda Pulls The Strings Behind M23’s Capture Of Goma And The Kivu

“I remember… The hills faded away. The road went up in difficult bends to climb a high mountain range. At the highest pass the wind blew from the bare peaks. And there were so many, and they looked so alike, dead arenas, extinct craters, wild flanks, and deserts, that one believed to have arrived at the end of the world.”

Journalist and novelist Joseph Kessel wrote these words in 1953 as he arrived in the volcanic region in the heart of Africa, the Kivu. Of his travels across declining colonial territories of East-Africa, he describes among many things, the beauty of the mountainous Great Lakes region against the backdrop of a society torn between modernisation and the cultural roots of ethnic social order.

Of the social divide between the minority Tutsis who ruled the region around Rwanda for centuries, and the majority peasant class Hutus, he claimed already then: “Nowhere in the world had existed, so close, so tangible in time, such age-old grandeur and beauty. Nowhere had their ruin been so fast.”

Decades later, in 1994, Hutus revolted against the Tutsi ethnic minority, slaughtering 800,000 in what became known as the Rwandan genocide. As the Tutsi’s regained control of the country under the leadership of Paul Kagame (the president of Rwanda still today), Hutus fled to what was then neighbouring Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The refugees were hunted by Rwandan forces and Tutsi Congolese rebels based in the eastern Congo across the late 90s during the two Congo Wars, many perishing from hunger, exhaustion, and murder by armed forces. When a peace agreement was reached in 2003, a UN peacekeeping mission known as MONUSCO based itself around the Lake Kivu area to defuse the tension in the region. But the conflict endured.

Since 1996, war in the Kivu is estimated to have cost over 6 million lives. Small rebel militias have sprung from the Congolese hills, many in some form opposing the Congolese government, and many also led by Tutsis. One of these groups, the Mouvement du 23 Mars (M23), managed to seize much territory in 2013, including the town Goma on lake Kivu, bordering Rwanda.

Though a peace agreement was reached, the M23 has maintained its presence in the region since, undeterred by the deployment of UN blue helmets, as well as Congolese armed forces and humanitarian efforts. Frustration with MONUSCO’s failure to contain rebel militias has swelled recently, and the mission has slowly been phased out since September 2023, to be replaced by troops of the Southern African Development Community.

Since then, the M23 has regrown into a force capable of controlling the region. In the past year, smaller militia’s such as Twirwaneho or Biloze Bishambuke have joined M23’s forces, as has a political opposition group called Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC), strengthening the hold over parts of Ituri and the South Kivu region.

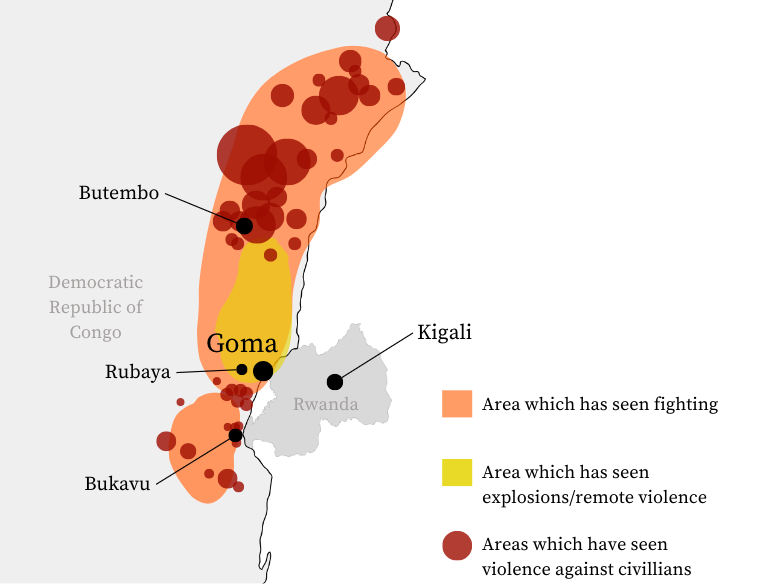

In April, the M23 seized Rubaya, a coltan mining town which generates $800,000 worth of trade and production taxes per month. With MONUSCO’s disengagement, the M23 progressed in its advance across much of the region, closing in on Goma, which was finally taken on the 29th January 2025. Yet if the M23 rebels have reclaimed much of the Kivu in the past year, it is not entirely due to MONUSCO’s waning presence.

Fighting in the Kivu in 2024

For ethnic affiliations ‘protecting Tutsis’ and its grasp over much of the DRC’s mines, M23 has been “systematically supported by the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF)”. Though Kagame denies it, the UN and the DRC have accused him of providing military equipment and soldiers to the group. One estimate suggests that as many as 4000 Rwandan troops were among the more than 8000 rebels who took control of Goma a few weeks ago.

The War for Minerals

Rwanda is a relatively small country, especially when compared to its giant neighbour, the DRC. It has mineral reserves of Tin and Coltan (Coltan is a mixture of Tantalum and Niobium, known for its value in the production of consumer electronics) — but they are nowhere near the scale of the Kivu’s resource wealth. And yet, a paper published in 2018 by the Goethe University Frankfurt claimed that in 2015, “Rwanda accounted for about 37% of global tantalum production, [while] the DRC accounted for about 32%”.

The same study found that in spite of low traceability and general knowledge of reserves, Gold is one of Rwanda’s largest export commodities, making up 13% of exports in 2016. They claimed it was “unlikely” this was due to poor observation data, but rather due to the fact that Rwanda, which has “no reliable statistics on its gold production”, is no doubt getting much of it illegally from across its borders.

Between 2014 and 2016, revenues on Rwanda’s Gold exports surged from $8.1 million to $80.06 million. Around that time, in November 2015, a UN report found that an unlicensed mineral exporter based in Bukavu, DRC, declared an export of approximately 270kg of Gold, from Rwanda to Dubai. This is more than three times the amount of Gold the South Kivu officially exported in the same year.

The US treasury also estimated a few years back that over 90% of the DRC’s Gold is smuggled abroad to countries such as Rwanda or Uganda for refining and exporting. In 2022, the Financial Times reported that according to DRC officials, up to $1bn worth of minerals were smuggled illegally from the DRC into Rwanda.

Yet the country’s prosperous mineral exports are not even a necessary metric to reach conclusions. It’s geography alone fits the bill, or rather, doesn’t. Guillaume de Brier, a spokesman for the International Peace Information Service, claimed: “When you look at the geological composition of Rwanda, it’s not possible that they mine what they export.”

Under Rwandan law, the country can claim the origin of minerals if a value of more than 30% is added once in the country. This could include processing or refining procedures. Rwanda’s mining sector is mostly dominated by artisanal mining, and generally suffers from a lack of traceability and due diligence procedures due to high costs on producers. So when many of the Kivu’s minerals pass through Rwanda on their way to the ports of the Indian ocean, Kagame can easily claim his share.

Trade Routes of Congolese Minerals

This means that, on a more fundamental level, Rwanda has much to gain from continued instability in the Kivu. The UN estimates that at least 150 tons of Coltan were illegally exported to Rwanda after M23 seized the Rubaya mine. In light of this, the argument that Hutu extremists responsible for the genocide still pose a threat to Rwanda, is largely a pretext for Rwanda’s continued presence in the Kivu. Support of the M23 is merely an economic strategy to continue extracting and plundering Congolese resources.

And at least to some extent, this pillage is also supported by international observers. For many western countries, notably the US, engaging a trade relationship with the DRC is blocked by restrictions on trade with war-zones and ‘conflict-minerals’. It is why over the past decade, China has held a vast monopoly over much of the DRC’s mining industry. Trading with Rwanda, also called the Singapore or Switzerland of Africa, is considerably less problematic.

Kagame has extensively lobbied for strong relations in Europe to support his regime, notably offering to take refugees from European countries. The EU also signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Rwanda, which could see as much as €900 million investments flow into the country to increase due diligence and traceability in the country’s mining sector, and the fight against illegal trafficking.

To some extent, this may uncover the current value-chains in which Rwanda benefits from Congolese minerals. Given Kagame’s reputation though, it is not likely to evolve much. Far too tempting is maintaining his unsanctioned support of M23, which now has control over much of the Kivu, including most of the hills that make up the Rwanda-Congo border. It would mean that, as in Kessel’s Rwanda of the 1950s, the mountains and volcanoes of the Kivu will continue to bear witness to a dispute between its ethnicities, and a fight over its minerals.