The Commons: Controversy around 'Rule Britannia' and the Legacy of the British Empire

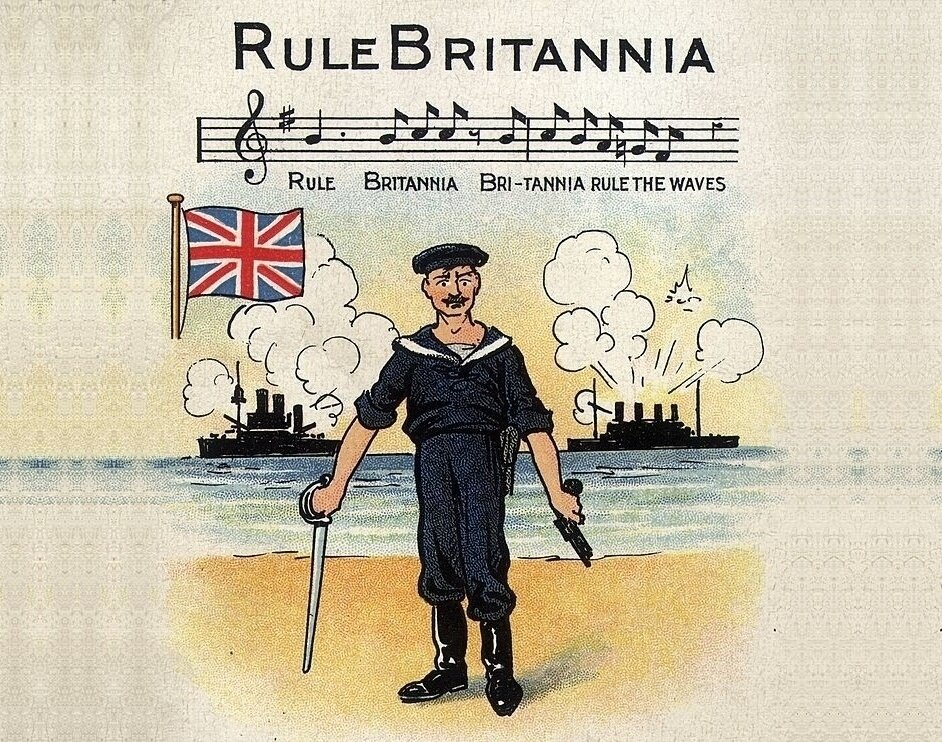

Hulton Archive / Stringer

As the UK continues to face a racial reckoning, “Rule Britannia” is just one of the more recent symbols of Britain's past to come under fire. The song, performed annually at the end of the BBC Proms, has been struck from the plan this year – or at least the lyrics have.

For many, the song is the symbol of British identity, patriotism, and pride – to think of the Last Night of the Proms without a triumphant performance of “Rule Britannia” and “Land of Hope and Glory” feels almost anti-British.

Controversy around these songs is not new, though 2020, a year of renewed racial justice following the murder of George Floyd, has provided a confluence of perfect situations to make a change. Not only has global support for Black Lives Matter and other decolonization projects grown in the last 6 months, but the world is still at the grips of COVID-19. Part of the BBC’s rationale behind omitting the lyrics of these songs is due to pandemic regulation. Understandably, the event will not be attended, even “socially distanced singing by the audience would be a health risk.”

The BBC’s decision has spurred what many are referring to as a “Trump-style culture war.” First to declare their anger at the proposal was the historically center-right Times. “Rule Britannia faces axe in BBC’s ‘Black Lives Matter Proms’” headlined the Sunday paper on August 23rd; The authors suggested that the songs would be removed from the program to appease the Black Lives Matter movement.

The piece struck a chord with Times readers, with one letter to the editor claiming that “Instead of helping ethnic communities in the UK, the BBC is driving an even larger chasm between them and the white community, which I believe will only cause more resentment and trouble in the future. There should be no such thing as Black Lives Matter all lives matter.” For many, the songs are patriotic, singing the lyrics loud and proud evokes a distinct feeling of being British. However, the lyrics themselves are said by some to glorify the British empire – the legacy of which many think Britain should address.

The lyrics of Land of Hope and Glory include “Wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set / God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet,” evoking what in the US could be referred to as a Manifest Destiny complex. As well, while ‘Rule Britannia’ technically predates the expansion of British rule, the song’s popularity grew with the growth of the empire. Many find issue with the line “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves,” a lyric “placing the 18th-century anthem in the middle of 21st-century culture wars about Britain’s colonial past.” Much like debates around the national anthem in the United States, the lyrics of these songs seem to celebrate the expansion of Britain and the oppression of millions that the empire involved.

Those upset with the removal of the songs’ lyrics claim that this is yet another attempt to “erase” Britain’s past. Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden tweeted that “confident forward-looking nations don’t erase their history, they add to it.” The question is then, what does adding to it look like? For those arguing the songs’ removal, this decision by the BBC is making history, not erasing it. For BAME Britons especially, these songs are not about British pride, they are about a pride of the Empire and those it represents. Wasfi Kani, chief executive of Grange Park Opera born to Indian parents in London, spoke to the Times about this feeling, saying: "I don't listen to Land of Hope and Glory and say 'thank God I'm British' it actually makes me feel more alienated. Britain raped India and that is what that song is celebrating." The Empire is something to celebrate for those who benefitted from it, namely, white Britons. The most recent census indicates that 80.5% of the population of the UK identify as “White British,” with 19.5% of the population that do not sit under that identifier. Many ask – If a song is to signify British pride, should it not resonate with the whole of the country? The thought of ‘erasing’ history makes it seem as though these songs, symbols of Britain’s sinister past, do not have current ramifications. Factually, this isn’t true – for many, the Last Night of the Proms alienates them, year after year, because of its reliance on these controversial lyrics. This is not a matter of erasing history, for many BAME Britons and allies, it’s a matter of historical sensitivity – a hope that Britain can begin to address its sinister past.

As this is a debate of national importance, Downing Street made sure to comment. A spokesman for Number 10 said that “the PM previously has set out his position on like issues and has been clear that while he understands the strong emotions involved in these discussions, we need to tackle the substance of problems, not the symbols.” For many, this feels a lackluster response – if the songs are symbols, are not the sentiments they glorify the substance? The substance may well be the alienation that BAME Britons feel today, in 2020. This song, though a symbol of a larger problem, is part of what substantiates the problem today. To hold British pride on the grounds of the Empire may be to continue to ignore the murder and theft undertaken by the expansion project itself. For many, the substance of this issue is Britain’s very ability to ignore the more grotesque aspects of its history – thus, addressing the lyrics of songs such as these is part of reckoning with the issue as a whole.

Yet again, Britain finds itself in the midst of a major cultural debate over what would seem to be a simple thing – British Pride. Much like with the tearing down of statues in recent months, center-right figures have taken the position that ‘erasing’ history is not the answer – though, they haven’t given a hint as to what the answer should be. For some, statues of slave owners and songs that celebrate the Empire – objectively a large part of British history – are merely symbols; they do not need to be removed. For others, these symbols have current effects on their lives. These statues and this celebration of British expansion add to a sentiment in the UK that is exclusionary to the nearly 20% of the population that does not identify with that history. A celebration of the Empire for some, is a celebration for many of lands stolen. For BAME Britons, many whose parents and grandparents saw the removal of their culture and their national pride, the Empire is not something to celebrate. The Empire does not make them feel ‘prideful,’ its alienating, reminding them of the way they are still excluded from what is considered ‘British.’