The 1789 Discourse: Gandhi On Self-Rule

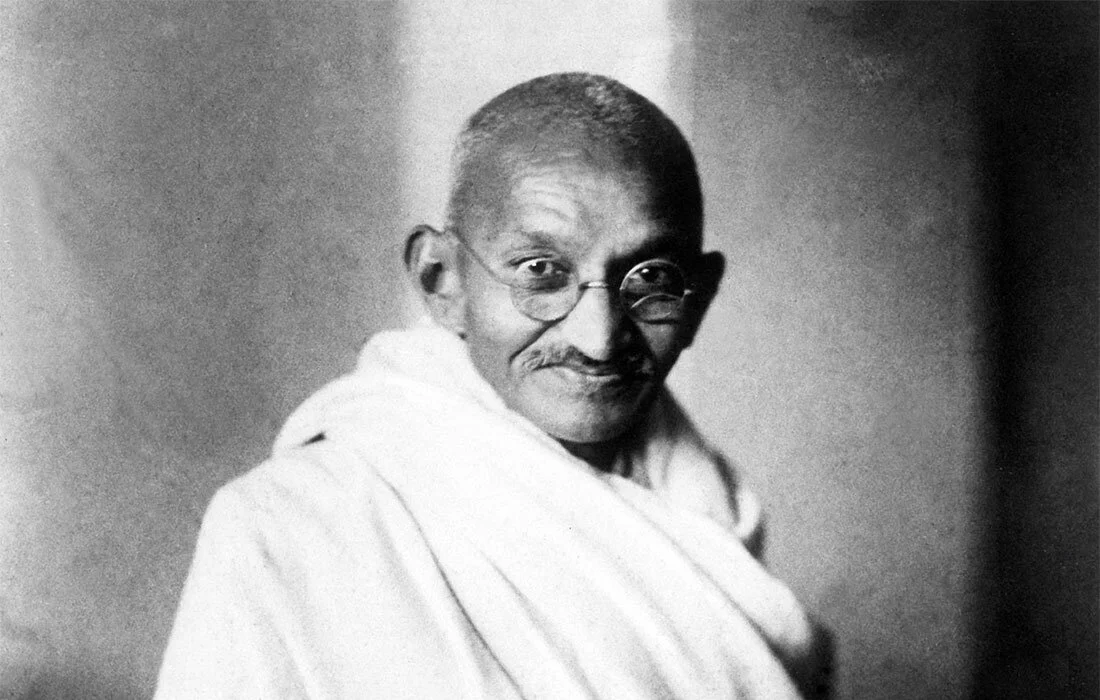

Dinodia Photos

Mahatma Gandhi is one of the most influential figures of the modern era for his profound and unwavering advocacy for nonviolent resistance. His words and actions, as David Runciman of TalkingPolitics puts it, “were not sufficient for Indian independence, but were undeniably necessary”. Gandhi’s most influential work, Hind Swaraj or Indian Self-Rule, was written in 1909 and banned by British authorities as “seditious”; in Hind Swaraj Gandhi outlines his fundamental spiritual beliefs and condemnations of oppression in Indian society as well as the world abroad.

The East India Company, or as Gandhi refers to it Company Bahadur, officially solidified its authority in India after they overthrew the Nawab of Bengal and established a puppet government in 1757. While the company had consolidated power and driven out all other competition, their power came to an end after the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. The British government deemed the company unfit to maintain control over the land and thus seized its assets and officially occupied the subcontinent.

As a young man studying law in England, Gandhi became very well versed in Western philosophy and civilization, but he deemed the core principles of its existence as a form of the disease. Gandhi deeply wished for India to become self-governing, however, he was very emphatic in preventing the same Western systems of leadership from infecting Indian public life. In Hind Swaraj, Gandhi considers the British Parliament, “like a sterile woman and a prostitute”, because of its inability to produce any good and constant change in leadership.

Gandhi’s commentary on the affairs of the English Parliament seems like an applicable critique to democracies and republics at large. He saw Parliament’s inability to perform the functions it was voted into office for as a symptom of self-interest and corruption that places loyalty to party and power over country and welfare for all.

Furthermore, Gandhi considers the media in England, the newspapers, as entirely dishonest yet the public’s adherence to it was on par with holy scripture. Gandhi repeatedly denounces the “sheep” mindset of blindly following an ideology or a mindset that one cannot conscientiously dissect and conform to or reject. Gandhi asserts that the principle flaw of “civilization” itself, more specifically Western Civilization, is bodily welfare as the principal objective.

This idea of swaraj, or self-rule, that Gandhi advocates for India are less in simple terms of civil governance, but he deems holistic governance of the individual’s own actions and desires as the most essential element to true Indian self-rule. With this standard, Gandhi advocates for the utilization of satyagraha: a form of nonviolent resistance.

In The Selected Writings of Mahatma Gandhi, Gandhi discusses the principal difference between Passive Resistance and satyagraha; Gandhi considers the connotation of Passive Resistance as if it were for the weak, however, he asserts that satyagraha is Civil Disobedience in the face of unjust laws. How cowardly is the person firing the canon versus the man who smiles staring down the barrel? Gandhi’s philosophy could quite possibly be one of the most powerful forms of individuality because of the disregard for the body and outside influences and the sacredness of the morality dearly held within the individual.

Gandhi considered this “truth force” of civil disobedience to be a means of securing rights and liberties through suffering. Suffering is almost a virtue in Gandhi’s eyes, however, he greatly condemns the suffering brought about by globalism and the effects of industrialization. Gandhi has a justifiable yet almost unhealthy disdain for the machines that permeate his society at the time of Hind Swaraj. Most specifically he condemns the evils of the railroads and the injustice of the local Indian weaver.

Gandhi considered railroads as facilitators of evil, and he claimed they so effectively destabilized Indian society by decreasing public health. Gandhi considered good actions and results to take some time to effectively accomplish, but evil could be instantly accomplished. In a time such as the current pandemic, Gandhi’s philosophy on travel might hold water, if he didn’t have such a blatant denial of Western medicine and doctors.

Granted, his concerns with Western medicine were definitely justified by the abuse and oppression of the British dominion, however, this outlook advocates denial of physical and technological advancements for the sake of spiritual empowerment. Gandhi’s concerns with industrialization were nothing new under the sun since the industrial revolutions of countries all over the world wrought an economic reckoning little would be prepared for.

Indulging in the fruits of the world were immoral in the eyes of Gandhi, and he condemns the pursuit of monetary success as a vice that has separated humanity from God. Industrialization and technology were muddying up the waters of moral consciousness and humanity’s respect for any form of deity.

“Money renders a man helpless. The other thing which is equally harmful is sexual vice. Both are poison. A snake-bite is a lesser poison than these two, because the former merely destroys the body but the latter destroy[s] body, mind and soul.”

This emphasis on the spiritual fulfillment and attention that Gandhi advocates could be directly attributed to the strict adherence to such a doctrine as satyagraha. Nevertheless, Gandhi’s worldview and philosophy did little to discourage the technological progress of society and the parliamentary structure of the modern Indian government.

Gandhi made a very emphatic assertion against the traditional Hobbesian view of the human state of nature since he believed that civilization and greed interrupted the overall peaceful nature of human interaction, but how far can his philosophy go when the world encounters Nazis breaking down their walls and storming their cities? Could nonviolence be sustainable against such an entity that has unified industry and state while totally disregarding the principles of God or even basic elements of human decency?

Gandhi’s philosophy was uncompromising and would never condone a violent retaliation no matter how justified, nor would he support allowing fear to drive citizens' hearts into voting for a populist who could guarantee sweet nothings. Gandhi’s approach might have inspired social activists like Martin Luther King Jr. while his methods brought universal attention, but does this mindset make its adherents capable of standing by as the weak and the innocent are oppressed and slaughtered.

In Gandhi’s view, this would even still necessitate his nonviolent approach because individuals must suffer for the security of rights so that spectators might rally to the cause. While Gandhi still influences movements today, human nature never fails to revert to the Hobbesian safety blanket of the state.