Checkpoint: The Electoral College, Democracy Or Tyranny Of The Few

Clay banks

Background

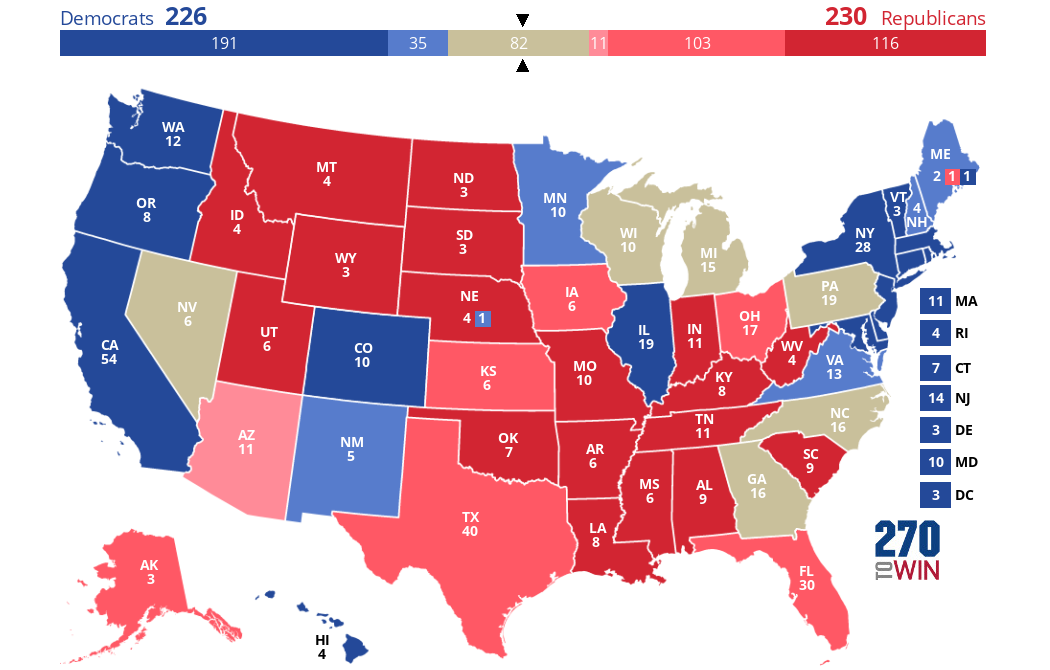

The Electoral College, a fundamental piece of the United States presidential election process, is again pushed to the forefront of the nation's concerns as America prepares for the 2024 election. Recent news articles and electoral map projections demonstrate the intensified significance of swing states like Nevada, Arizona, Georgia, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, raising more questions about its role. Former president Donald Trump is ahead in five of the six swing states (47 percent versus 45 percent), only leading by a slim margin of two points in Wisconsin. The election in November offers a debate about the impact of the process on democratic (and, essentially, American) principles, particularly relating to the protection of smaller states versus the potential disenfranchisement of voters in densely populated areas. While the country's most populous states boast the most votes, respectively, rules put in place at the country's founding make it so states with a fraction of the citizenry have more power than is proportional. For example, California's registered voters stand at 22,114,456 people and Montana's at 745,103, making one Electoral College vote the equivalent of 409,526.96 people in California (54 EC votes) and 186,275.75 people in Montana (4 EC votes)–––this means that Montana's voters (Republican) have 2.198 times more voting power than someone in California (Democratic). As voters struggle with this controversy, some vital questions emerge: Does the Electoral College, with its historical roots and evolving significance, adequately balance the representation of diverse states and citizens? Does this system align with the fundamental democratic tenet of "one person, one vote," and if not, what avenues exist for encouraging fairness?

The Electoral College: A Historical Perspective

The Founding Fathers of the United States conceived of the Electoral College during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, meaning to be a compromise between the election of the President by a vote in Congress and the election of the President by a popular vote of qualified citizens. The framers, operating in a country of just under 4,000,000 people (3,929,214 in 1790), grappled with crafting a system that preserved states' rights and prevented a concentration of power in densely populated areas. Respecting the interests of large and small states was necessary during this period, and the Electoral College was a solution that blended elements of direct and indirect election. Each state would have electors equal to its total representation in Congress, combining the number of Senators and Representatives and addressing worries about states with varying populations. Still, America's ten largest urban places supported populations smaller than 34,000 people. The original intentions of the Electoral College were honorable, established in the hopes of an equilibrium between the dominance of more populous states and minority rule. Though questionable 237 years later, this foresight structured the Electoral College as a mechanism to distribute influence across the states and has had implications echoing through three centuries. Over time, modifications like the 12th Amendment (which refined the procedures for electing the President and Vice President) and the 23rd Amendment (which granted electoral votes to the District of Columbia) have shaped today's system, where there are 538 electors in all and a candidate needs the vote of 270 of them to become President. This evolution reflects an ongoing dialogue about the delicate equilibrium between the need to maintain fair representation and the imperative to prevent the tyranny of the majority or the minority.

Americans Favor Popular Vote Over Electoral College for Electing a President

Protecting Smaller States Or Disenfranchising Voters?

As of 2023, most Americans favor moving away from this strategy, with 65 percent advocating for change in the current system, so the prospect with the most votes wins. Democrats, whose candidates have been denied the presidency by the Electoral College four out of the five times in American History that a contender became President despite losing the popular vote (the other was in 1824, and all hopefuls identified with the Democratic-Republican Party). Data shows that 82 percent of Democrats support moving to a popular vote for President, but only 47 percent of Republicans agree. The argument in favor of the Electoral College often revolves around its perceived role in shielding smaller states from marginalization in the presidential election process. Proponents argue that without this system, candidates might focus exclusively on densely populated urban areas, neglecting the diverse circumstances of other communities. Conversely, this safeguard for sparsely populated states such as Alaska and Wyoming stokes anxieties about voter debilitation in cities and states like California and New York. Instances where large urban centers with significant populations feel overlooked and neglected by candidates seeking to secure crucial electoral votes, have become points of contention. Unfortunately, because of this system, presidential nominees focus on campaigning with battleground states in mind instead of their tried-and-true voters. The influence of swing states, often with a history of political unpredictability, hold disproportionate sway in deciding the outcome of elections–––while they can feel pivotal, their prominence inquires about the fairness of a system where certain states consistently garner heightened attention, potentially overshadowing the concerns of others.

Democrats More Supportive Than Republicans of Choosing President by Popular Vote

Navigating Fairness And Democratic Representation

Navigating justice and democratic representation within the intricate framework of the Electoral College poses considerable challenges. Critics argue that the winner-takes-all approach in most states can amplify disparities and limit the diversity of voices heard. Nevertheless, a potential reform to address this issue involves exploring alternative allocation methods, such as proportional representation, where electoral votes are distributed based on the percentage of a candidate's popular vote in a state. Such a modification would better reflect each state's manifold range of opinions, ensuring a more accurate portrayal of the electorate. In pursuit of a more equitable system, values centered on inclusivity, social justice, and the well-being of all citizens are paramount–––incorporating such ideals into reform could emphasize the importance of ensuring the electoral process benefits all citizens, irrespective of geographical location or population density. Prioritizing the entire nation's interests by defending states of all sizes and acknowledging the apprehensions of areas of all population densities is a more nuanced approach, upholding the core principles of democratic governance.

Summary

As the 2024 presidential election looms, the enduring doctrine of "one person, one vote" resonates as the basis of a genuinely democratic society. The Electoral College's flaws, highlighted in the past election between Clinton and Trump, underscore the need for continued scrutiny and improvement. Americans must engage in informed discourse, utilizing various platforms to amplify their voices and draw attention to the systemic issues within the electoral process. Through civic engagement, grassroots movements, and advocacy for change, citizens can collectively work toward a more impartial and model electoral system that reflects the democratic ideals upon which the nation was founded. The journey toward a more perfect union demands an ongoing commitment to ensuring that every vote counts and that the democratic process remains resilient in the face of evolving challenges.