Dancing After Ten Years In A Wheelchair: The Stem Cells Factor

The protagonist offers himself up to the mercy of the world’s most powerful technology. To get past some mystical, physical blockade, they turn to the world’s most promising untested technologies, offering themselves in sacrifice in the name of progress. Hollywood loves this script, fitting the storyline to countless films, like Deadpool, where the operation gives the protagonist super-human powers, or The Fault in Our Stars, which takes a more pragmatic approach to medical storytelling. Regardless, the ending always exists in some precarious balance between medical success and failure, between life and death. Sometimes, though, real life trumps Hollywood scriptwriters and the ending, for some patients like Roy Palmer, is nothing but blissful.

Because of a severe case of Multiple Sclerosis, Palmer, a middle-aged man from Gloucester, had lost feeling in the legs, and had, for the better part of 10 years, been confined to a wheelchair. Only about a month ago, a now-viral video of Roy Palmer surfaced, showing the man miraculously dancing along the upbeat tunes of Drake’s In My Feelings. What happened in between these two moments, one might ask? Roy underwent a novel, uncertain, highly risky operation known as Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation, HSCT for short.

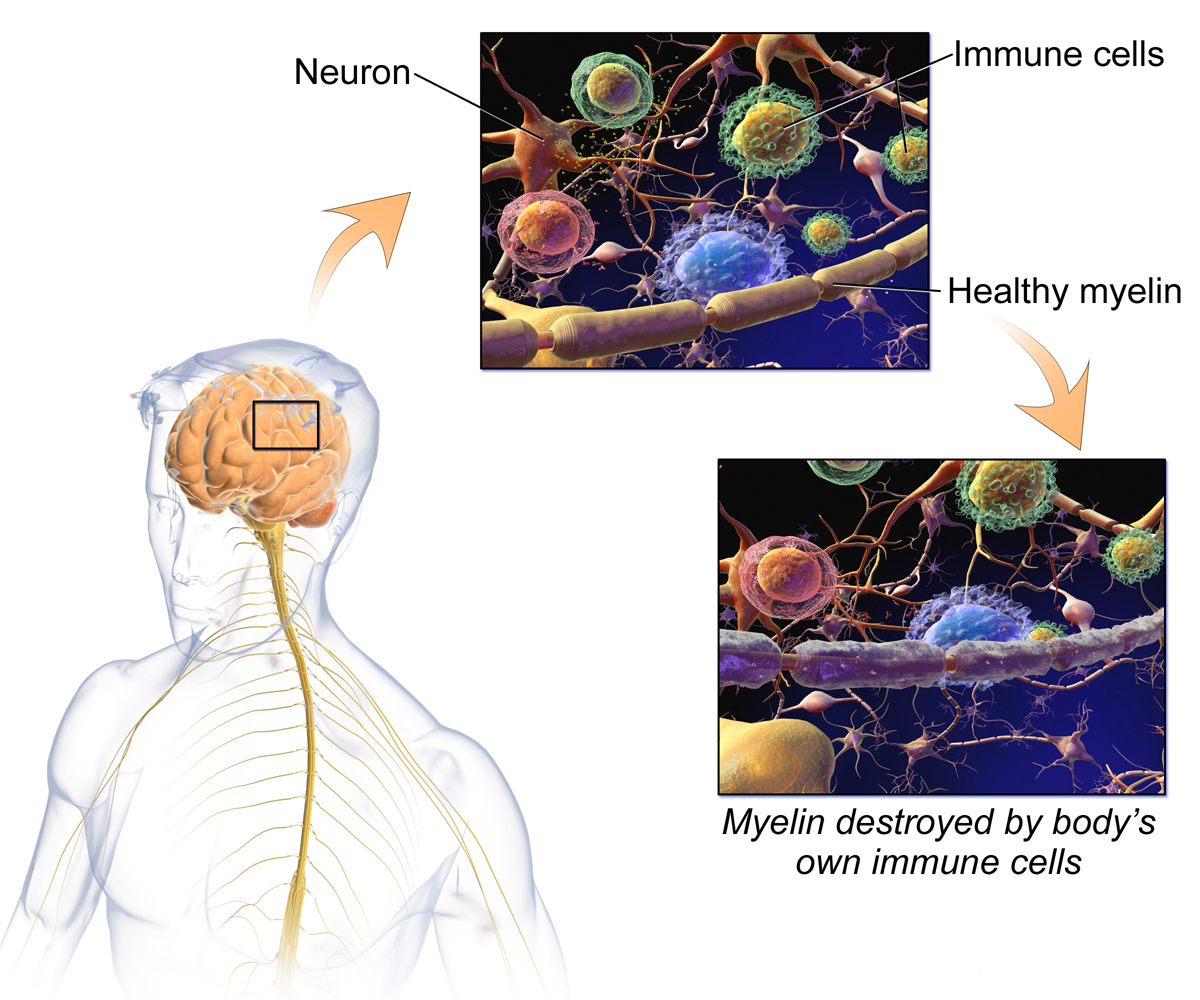

To begin with, Multiple Sclerosis (MS, for short), is a vicious autoimmune disease, for which medicine has yet to determine the cause. What is known, on the other hand, is that Multiple Sclerosis is a terrible deficiency of our own immune system, which turns its own cells against each other. As a matter of fact, the MS patient’s immune system will target the protective covering of nerves, in an attempt to do what it’s supposed to do for pathogens: digest them. As such, immune cells eat away at the myelin (a tough material found covering most of our nervous fibers) that covers neurons and nerves, deteriorating their efficiency. Sufficient exposure to this repeated practice yields a nervous system that is gravely damaged, causing disconnects between the brain and the more peripheral joints which it commands. The exact locations of these deteriorations are hard to track, and far from uniform amongst MS patients: some lose control of their legs, some of their arms, some of the different functions of the body. Regardless, the autoimmune disease is amongst the world’s most frightening for sheer viciousness of action and difficulty of treatment.

It’s no surprise, then, that 49 years turned to innovative medicine to ameliorate his own condition, which had left him without any feeling in his leg. As he was sitting in his living room, the BBC Program “Panorama” aired a special covering HSCT, a new, experimental treatment for Multiple Sclerosis, which showed patients entering the hospital in a wheelchair, and coming out walking on their own two feet. Palmer had no doubt, after years of wheelchair confinement, he was ready to try the highly risky, still novel procedure. Two days after HSCT treatment, Palmer regained the feeling in his leg and even began walking and dancing.

How Multiple Sclerosis damages the nerves’ Myelin sheaths.

What lies at the core, then, of this seemingly magical treatment? HSCT is, as indicated by its nomenclature, a form of stem cell treatment. Through chemotherapy, the commonplace practice for killing cells, HSCT targets the deficient immune cells, in an attempt to sweep them all out of existence, essentially wiping the patient’s immune system. After this powerful and highly dangerous selective killing of cells, surgeons remove some stem cells from the patient, either out of their bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood. These cells, which have the power to become any type of human cell they like, are then, in very crude terms, reprogrammed to be immune cells. Once they are successfully cultured, once they are enough to normalize the body’s blood cell count, the immune system is “restarted”, and the newly directed stem cells take over the role previously held by the defective immune cells. The procedure, then, is essentially a restarting of a defective human defense system. The faulty system of cells is killed and wiped out, and multipurpose stem cells are “trained” to (irreversibly) function as pristine immune cells. Once these are plentiful enough in population, they are allowed to take over, essentially replacing the entirety of the microscopic population.

Though the National Multiple Sclerosis Society still considers the treatment highly experimental, it seems to be analogous to a high rate of success for patients with no other major complications, like Palmer himself. After only two days, the man had regained feeling in his legs, and after some time still, he began walking and even dancing, embodying what is perhaps the most impressive success for HSCT’s still short history. “I haven’t felt that in 10 years”, he says to the BBC’s microphones, “it’s a miracle”. Yet, for the global medical panorama, Palmer’s story represents more than the miraculous transition from wheelchair to dancing. Rather, it represents one of the first public iterations of successful, unabridged, unprotected form of stem cell treatment in the United Kingdom. The procedure has, historically, been riddled with a complicated ethical debate, as the most versatile of stem cells were often taken from embryonic cultures, and might hence have gone on to create different human life altogether. Now, however, as is the case with HSCT, and with Palmer’s story at that, stem cells are removed from the patient’s own body, taking pluripotent cells from bone marrow and other tissue. These are then retro-engineered to become whatever they must, turning them, in this case, to the cells that make up our immune system.

Ethically, then, the debate has, in recent years, surely toned down. Yet, the sheer reach of stem cell treatment still has trouble being properly framed. The pluripotency of the cultured cells, even those that come from our very own bodies rather than embryonic cultures, has medical implications that, naturally, touch a myriad of different fields. The autoimmune disease field, will, surely, be revolutionized as more and more treatments akin to HSCT become available. The same, as science hopes, will occur for all fields where stem cell therapy is a viable, if not dauntingly attractive, route of action. Despite the dangers of experimental treatment, if Roy Palmer’s story has a happy ending, it is because it’s a daring one. Moving past risk and towards progress, it represents a guiding light that, hopefully, science will allow many to follow in the coming years.