Section 230: Your Internet, Your Truth

Westend61

“The public must be put in its place, so that it may exercise its own powers, but no less and perhaps even more, so that each of us may live free of the trampling and the roar of a bewildered herd.”

– Walter Lippmann, The Phantom Public

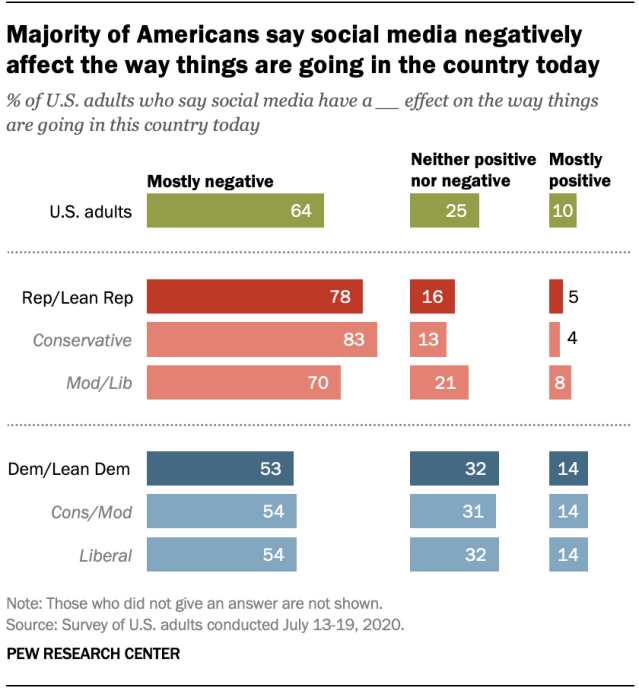

There is a profound sentiment among Americans today that social media is doing more harm than good. There doesn’t seem to be much faith in American politicians either. Perhaps it is in part because they only ever seem broadly compatible with the public they purport to serve. They only ever say just enough – nothing too specific nor too vague – to keep their base happy. It is an absurd performance of ideological elusiveness and adherence, directed by the roar of a herd.

Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and Google all serve the same master as the politician: vox populi. Ironically, this is in many ways antithetical to the purpose of free speech. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act provides no check for the public’s tyranny, it doesn’t require neutrality either. Therein lies the danger of a law which protects both providers and users of “interactive computer services” from the responsibilities incumbent on a “publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

There is no shortage of valid criticisms of President Trump or right leaning ideology, and this article is by no means concerned with defending conservatism. However, concerns with Section 230 have often been dismissed as alarmist attempts to shield conservatives from what they perceive as censorship. This is, fundamentally, not an issue of political leaning, rather a sociopolitical examination. The lack of liability under Section 230 is fostering a pernicious environment online, putting first amendment rights at risk.

It’s often argued that Section 230 aims to maintain free speech on the internet, and this is wholly valid. The protection it provides means that internet users can – for the most part – interact with social platforms to communicate more freely and organize around issues or ideas that might not otherwise have a platform for expression. It can provide camaraderie for those who might not have an easy time finding it in the proverbial public square. Moderators have no responsibility to interfere in these interactions save for a few exceptions like federal criminal and intellectual property laws.

Yet, Twitter and Facebook flagging or “fact checking” certain tweets and posts, subtly supports or condemns certain narrative ideologies. They can discreetly subvert an ideology or perspective while hiding behind some semblance acting in “good faith” or the “public’s interest.” Section 230’s nebulous nature provides this plausible deniability.

The “good faith” provision of the law allows internet platforms to remove or “restrict access to” anything that the “provider or user considers” to be offensive. Ideally this should protect content from being removed or flagged in a manner inconsistent with an act taken in good faith. In practice, however, this distinction is lost. Effectively, Section 230 is a vague, blanket protection from any liability for censoring content on social media platforms.

How could legally shielded for-profit corporations, that sell you to advertisers for massive amounts of money, ever maintain freedom of speech within the current polarized environment?

A Sticky Situation

How does the law acknowledge social media companies as private businesses, yet simultaneously hold them liable for actions they take in regulating their own platforms? From the neoliberal perspective this is unAmerican. You have the right to freedom of speech in the public square, but not in the bar that does business alongside it.

There are 2.6 billion Facebook users, 2 billion Youtube users, and 326 million Twitter users. If these companies are liable, they would have the impossible task of moderating everything or nothing. If you can think of it, you can probably find it on the internet, and that’s precisely the thing that makes the internet so delightfully useful. Reforming Section 230 puts that at risk.

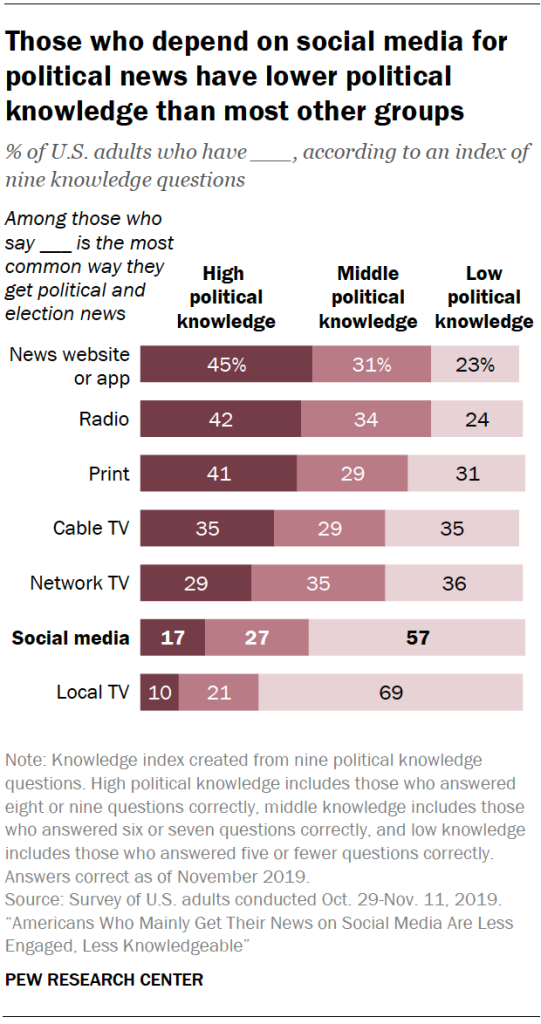

According to a 2018 Pew Research study, 34% of U.S. adults said they prefer to get their news online. Employment in digital newsrooms also increased by 82% between 2008 to 2018. Everyone has the right to choose their news source, but many outlets have become increasingly biased, and that’s to say nothing of gossip stories or blatant lies.

So maybe the internet has outgrown the practical application of Section 230 since its 1996 inception. If it’s necessary to bring it up-to-date, it’ll have to be done very delicately. Social platforms have become a necessary part of everyday life. They’ve become practical tools for effective communication and education, but they’re also private businesses with a uniquely enormous amount of influence.

As Facebook and Twitter increasingly yield to outrage and cancel culture, the risk of mob-controlled gatekeeping on these platforms increases. It is impossible to moderate everything on social platforms with so many users, but they must moderate some things. In those ‘some things’ they moderate, they surely must moderate anything harmful or anything that causes pain. As private businesses, social media giants can and will interpret pain and harm in-line with what will protect their advertisers from public outrage.

Prager University v. Youtube

Consider the Prager University case, rather tame conservative cartoons were posted on Youtube covering subjects like abortion and gun rights. Youtube tagged dozens of the videos for “Restricted Mode” and blocked third-party advertising. Prager U sued, arguing that Youtube describes itself as a neutral platform, supporting free expression of ideas, but then violated Prager U’s rights to freedom of speech.

The court ruled that Youtube and its parent company Google are “private forums” despite their public-facing platforms, thus are not “a public forum subject to judicial scrutiny under the first amendment.” Neither Google nor Youtube are platforms traditionally viewed as biased – it can only be inferred. Yet Prager U’s defense had no problem finding unflagged videos covering the same subjects from the liberal perspective.

This is the most pernicious aspect of social media moderation: a lack of transparency in regard to their guidelines and rule enforcement. I imagine it’s rather clear – at least to American audiences – where CNN and FOX lie on the political spectrum. When watching or reading their content a bias is naturally expected. People don’t typically engage with social media platforms in the same way, making any potential bias on their part especially harmful.

One cannot find any evidence that Youtube in any way addressed the ‘Adam Ruin’s Everything’ videos. A video series where numerous episodes have been denounced by other Youtubers for their blatant historical inaccuracy and left-leaning bias. So why was Prager U censored? The only answer Youtube provided, according to Dennis Prager, was that the content was “inappropriate for children.”

Demanding Action

Organizations and users themselves are pressuring social media giants to do more to “tackle hate and harassment on their platforms.” Yet, what is being defined as “hate” or “harassment” is becoming increasingly ambiguous. The idea is that certain viewpoints are culpable or complicit in real world harm being committed. It doesn’t take a genius to see how an ad hoc subjective interpretation of “harm” or “hate” can be exceedingly damaging to productive discourse in both the social and political realms.

One would only find Prager U’s videos inappropriate if one was in ideological disagreement. This is seemingly a moot point, as this is true with every possible notion. However, here harm and offense are derived from being in opposition, not from being attacked. So is Youtube pushing its own ideological agenda or preemptively acting in-line with potential outrage – the roar of the herd? This isn’t to say that leftwing or liberal views are never censored, as was the case when Twitter suspended many Occupy Wall Street activists in 2018. The issue isn’t in the extremities, it’s in the cases like Prager U’s, where some ideas are given platforms whilst others are inexplicably flagged.

It’s telling that the CEO of Twitter said conservative employees ‘don’t feel safe to express their opinions.’ There is a censorious side effect of certain ideologies. As when an employee of Facebook publicly leaves the company because its political speech policies “facilitate a lot of pain.” Who could oppose such a moral-sounding claim? Certainly not advertisers and the recent Facebook boycott demonstrates their sensitivity.

Whose Truth?

Facebook and Twitter recently blocked a New York Post story detailing incriminating pictures and documents of Hunter Biden. A New York Times investigation on Trump’s tax returns and all the interpreted implications therein circulate without intervention. Both stories scrutinize the character and integrity of a presidential candidate, but only one is to be fact checked and suppressed. In this way political bias could lean so heavily on public discourse that it becomes doctrine.

The problem with misinformation is a problem of narrative. The herds of users on Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, Reddit – They get to decide which narrative will appear in a user’s feed and as people increasingly use social media to get their news, the more one narrative or another is taken at face value. Two sides of any story have the same dangerous potential to mislead and stoke fear among the public. Are Facebook and Twitter acting in “good faith” when they protect us from one narrative in favor of another?

It is taken for granted that the law is set to protect us from government tyranny – but what about the tyranny of mob rule? Just like the politician, social media platforms are beholden to money and public opinion. Unlike the politician, they often fill the role of subtle arbiters of public discourse on the platforms that have effectively become the modern-day public square.

Social media platforms are clearly bullied into catering to the loudest voices and Section 230’s broad nature shields them from the negative externalities that might arise from their capitulation. These externalities will no doubt playout most harmfully in the long-term, making them easy to ignore presently. Allowing the fear of perceived harm to silence opposing views quietly nudges the Overton Window toward something more dogmatic. This, of course, permeates throughout our culture bolstering tribalism and division.

There must be some mechanism or authority – whether by Section 230 reform or otherwise – that can prevent moderators of platforms from unreasonably, biasedly, or maliciously altering the content their users view. Simultaneously “the public must be put in its place” so that the trends and idiocy of a herd do not rule over reason, fairness, and freedom for the individual.

Otherwise, we risk fostering a cultural and political landscape where dogmatic ideologies dictate our perceptions, beliefs and social interactions. Without proper checks in place only a bewildered herd will be, well, heard. There should be no platform for voices that we have all agreed to reject, but we should also be exceedingly cautious of how we define such voices. Silencing views through vague interpretations of loosely defined sentiments is undemocratic and frighteningly underhanded. An open and transparent exchange of ideas in both our media and on our virtual public squares is the only way to maintain progress in an increasingly complex, globalized world.