Improving The Ballot: Political Division And Your Vote

LifestyleVisuals

People love simple dichotomies – Good versus Evil, Us versus Them, and of course, Democrat versus Republican. It’s a well examined topic in psychology, creating opposition helps shape our perceptions of ourselves. Yet no one could persuasively argue that the world operates this way. Whether we’re talking about nature, society, economics or any given mother-in-law’s personality – a myriad of interconnected layers are involved.

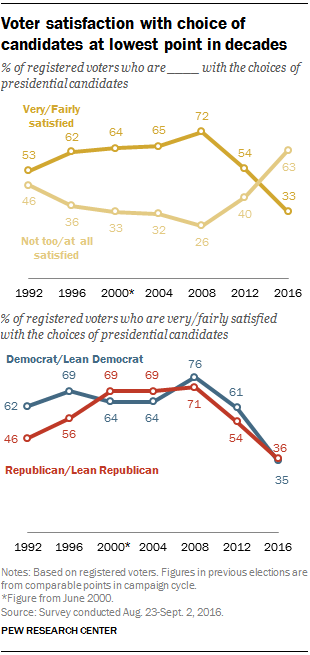

Something about the past two U.S. elections just doesn’t sit right with many people. Despite the high turn-out in 2020, it’s probably fair to say that people aren’t participating out of a unified sentiment of hope or change for the better. Their motivations, if not outright spiteful, are probably best embodied by the phrase “lesser of two evils.” Lack of trust – in both the government and each other – is making it difficult for America to move forward productively.

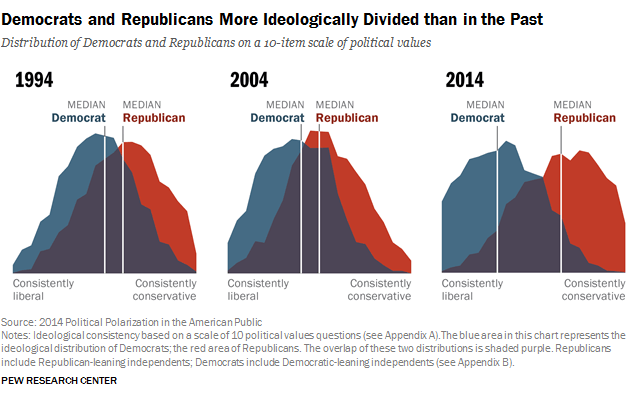

According to Pew Research, political and ideological polarization has widened dramatically since 1994. Either Americans really like the Us versus Them dichotomy, or something about the political system and the way Americans participate in it needs greater examination. In a complex world with complex problems, conforming political views along party lines only ensures focus on opposition at the expense of critical thinking and problem solving.

So what about Ranked Choice Voting then? Both Alaska and Massachusetts decided ‘no’ to this alternative voting method in the 2020 election. Yet, if Americans generally believe some structural change is needed, as Pew Research suggests, then a new voting method seems a good place to start.

Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) – also called Instant-Runoff Voting (IRV) or preferential voting – allows voters to cast a ballot naming multiple candidates ranked by preference. All registered voters could name their first, second, third, etc. preferences for a particular office. Then, whichever candidate receives a majority of first preference votes would win the election. If no candidate receives a majority then the candidate with the least first preference votes would be eliminated. The second preference on those ballots would then take the place of the eliminated first preference candidate. This process would continue until a candidate has a majority.

Ranked Choice Voting has already been implemented in the U.S. and is garnering quite a bit of attention. Starting in 2021 New York City will become the most populous city in the U.S. to use RCV. Maine already uses RCV statewide and 12 other states, including California, Florida, and Tennessee, use it for local elections.

The process involved is commonly criticized as being too complicated and confusing. While it certainly is more complicated than the bipolar system Americans are accustomed to, calling it confusing seems more like petty dismissal than genuine concern. The concept is relatively straightforward and creating more space for new parties, more candidates and less “Us versus Them” politicking is a noble idea that should be taken seriously.

Naturally, there are legitimate concerns for the system that opponents are quick to point out. There is a tendency for some voters to only fill in their first choice preference or to simply fill in too few preferences, inevitably rendering their ballot invalid during the elimination and recounting process. This is referred to as “ballot exhaustion” and it can easily lead to a candidate being elected without a true majority of votes.

For instance, a case study of the 2011 San Francisco mayoral race found that 44.8 percent of votes cast with only one listed preference were exhausted. In contrast, only 22.5 percent of votes listing at least three candidates were exhausted. Among a number of U.S. case studies these were the highest rates of ballot exhaustion and illustrate a major pitfall of the RCV process.

Opponents of RCV are also quick to mention that its implementation doesn’t necessarily bring about less campaign spending or less negativity in political discourse. In the case of the San Francisco mayoral race, the winning candidate Ed Lee spent more than $1.3 million. While this is significantly less than what is typically seen even for mayoral races, it’s still generally safe to say that RCV won’t put an end to the influence of money in politics.

The political divisions in Australia – where RCV is used to elect members of the House of Representatives – are often compared to the divisions in U.S. politics. Despite the country’s use of RCV, two political parties have consistently dominated Australian politics, the Labor Party and the Liberal/National Coalition. Clearly RCV isn’t a remedy for an “Us versus Them” attitude, but it’s worth noting that voting is compulsory in Australia, and RCV or instant-runoff voting isn’t used across all levels.

Ranked Choice Voting isn’t a cure-all for problems in U.S. politics, but it could be an encouraging change for the average voter. There are concerns that the confusing process and less straightforward outcome of RCV could affect people from disadvantaged and/or low income demographics. It would be unfair to expect the average person to have enough information to rank more than a few candidates during any particular election. However, RCV only asks voters to pay slightly more consideration to opposing options. If a new system begs the possibility of a positive political change this could incentivize a higher rate of genuine political engagement.

In the current plurality system, where’s the incentive for a Republican to vote in a state like California or New York which are considered solidly “blue?” How about a Democrat in Texas? Couldn’t these votes also be considered “exhausted” to some degree? Considering the low voter turnout and the number of votes cast for a candidate based on their likelihood to win or them being the “lesser of two evils”, it seems fair to say that the current U.S. electorate system is coercing votes that might otherwise be exhausted.

The United States is also a one-party state, but with typical American extravagance, they have two of them. — Julius Nyerere

Fairvote.org, a non-partisan organization that supports the adoption of Ranked Choice Voting, also touts the voting method as a partial fix for Gerrymandering. Allowing district lines to be redrawn for political advantage only helps to support the “duopoly” of U.S. partisan politics. Reforming the law so that districts are drawn by “independent redistricting commissions” and implementing RCV would “help promote fair representation of minority viewpoints.”

The most obvious and alluring feature of Ranked Choice Voting is the simple fact that every voter can always vote for the candidate they feel best represents them. If they don’t believe their candidate of choice stands a fighting chance of winning they can – and obviously should – add their second and third preferences to ensure their vote counts. This is also a feature said to encourage better behavior among candidates while campaigning. The prospect of being listed as a voter’s second preference could very well limit the level of vitriol in a candidate’s criticisms of their opponents. A survey from the Iowa Public Policy Center found that “people in cities using preferential voting were significantly more satisfied with the conduct of local campaigns than people in similar cities with plurality elections.”

When political feelings are as volatile as they have been in recent years a different voting system might just be enough to bring about genuine change rather than indifference and/or submission to a dominant political party. No political system is perfect, but with that in mind it’s about time Americans start experimenting with reform. Adopting a different voting method certainly won’t do away with powerful political parties but it could provide voters a threatening tool to better ensure that politicians represent the interests of the people they claim to serve.